Conflict

Conflict is any obstacle that conflicts with a character’s goal. Conflict is sometimes too narrowly defined as confrontation. While arguments, swordfights, and space battles are types of conflict, not all conflict is violent. Consider conflict an obstacle or a complication, something that makes a goal difficult to achieve.

Conflict represents an opposing force to your character’s goals. As a result, conflict introduces uncertainty: it’s less clear if your character is going to be able to accomplish what they set out to do.

Every scene should have some conflict. At the beginning of the scene (Point A) your character has a goal and they expect that by the end of that scene (Point B) they will have achieved that goal. If your character achieves their goal without difficulty, we have a boring story. But if we as writers make that path from Point A to Point B a crooked one, with lots of bumps, and unexpected twists, we create a worthwhile journey for the character—one the reader will want to read.

Types of Conflict

Person vs. Person

Person vs. Person

Two characters have different goals that don’t align. Modern drama is full of examples:

- two people want to lead the same team

- a husband might want to stay home and watch the football game, while his wife wants to go out to a movie

- each person on a date wants to go to a different restaurant

- one person on the team wants to spend more time planning the work, while another wants is impatient to start doing it

- an employee finds his manager’s leadership style too authoritative

Each of your characters enters a scene with their own agenda and priorities. Look for opportunities to have those priorities clash.

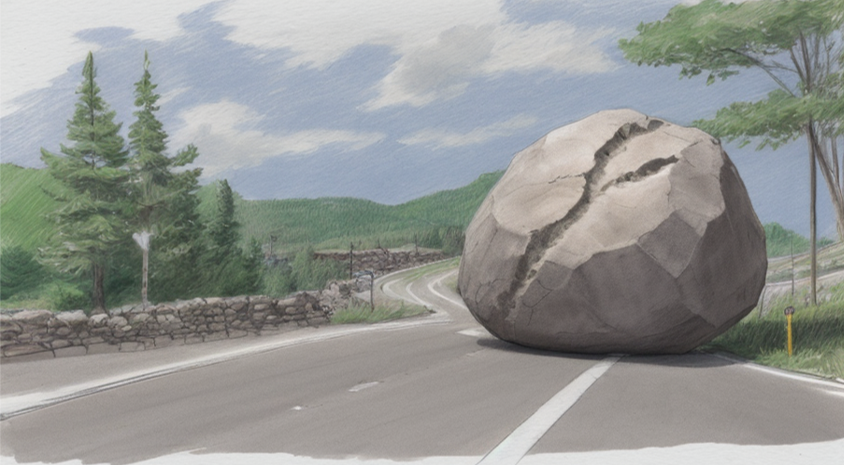

Person vs. Nature

Person vs. Nature

An animal or force of nature stands in the way of a character’s goal. Sometimes an entire story is built around this type of conflict, as in the novel The Old Man and the Sea, or the movies Castaway and The Martian. In these examples, the stakes are life and death, and hence the protagonist’s prior goals are replaced with the goal to survive.

Life and death stakes can still occur at the scene level, however “bad weather” might be considered a circumstantial difficulty.

- a flash flood or other natural disaster occurs

- a person in a tent spots a bear on the campsite

- a person needs to climb along a perilous mountain path to travel to the next village

Person vs. Self

Person vs. Self

Sometime a person is their own worst enemy. This type of conflict is often called an internal conflict or internal struggle.

Some examples:

- a person suffering from stage fright needs to make a speech

- a soldier needs to decide whether he should follow orders he considers immoral

- a person is unsure whether or not to tell a long time friend that he loves her

Person vs. Society

Person vs. Society

The rules or norms of society stand in the way of a character’s goals. This type of conflict is often seen in dystopian stories, like The Handmaid’s Tale or 1984.

Examples:

- a person wants to get to the hospital as soon as possible, but the posted speed limit will delay him

- a person in a rush to buy something at a store encounters a full parking lot, except for the handicap stall

Person vs. the Unknown

Person vs. the Unknown

Sometimes a character is up against an unknown or supernatural force. Typically, these conflicts are far more prevalent in the horror or paranormal genre than an isolated scene in another genre. Sometimes, however, the opposing force is unknown, and the character might believe it to be a supernatural (or unknown) entity. In this case, this type of conflict might overlap with the person vs. self, where the person struggles against a powerful (and believable) imagination.

For example:

- campers have been mysteriously disappearing

- there’s a strange noise in the basement that a character assumes is a monster

- a child imagines a monster under the bed

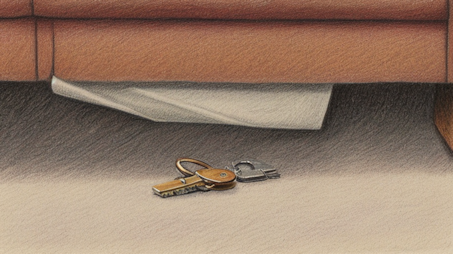

"Bad Luck"

Person vs. the "Bad Luck"

- someone needs to drive somewhere, but they misplaced their keys

- a person’s cell phone battery died

- the computer crashed

- the power went out

How much conflict?

Every scene should have some conflict. In fact, the conflict should take up most of your scene.

There might be one obstacle or many. The obstacles might be large or small.

How much conflict and how many obstacles is up to you. Consider the following guidelines:

- you need at least one obstacle/complication (otherwise there’d be no conflict)

- if you only have one obstacle, make it a big one

- I suggest no more than five obstacles in one scene (If you have that many obstacles to a single goal, the goal might be overly ambitious for one scene. Consider splitting the goal and having a separate scene for each.)

- use circumstantial difficulties sparingly (more than two in a single scene might appear too contrived)

- put the smaller obstacles earlier in the scene and the bigger ones later so that things get worse and worse (Shawn Coyn calls these “progressive complications”)

Why torture our characters?

As writers, adding conflict means adding misery into our character’s lives. Sometimes there are characters that we feel deserve suffering we dish out (especially the antagonists). Sometimes writers get attached to the characters. We adore them. Why should we inflict such hardship on them?

In short, conflict shows readers how your characters cope with adversity. Some characters will grab the bull by the horns. Others might withdraw and strategize first. Some might frustrate easily. Some might learn from the experience.

You might want use conflict to demonstrate your character’s specific traits, or talents, or skills. For example, if your character is particularly smart, you may want to give them specific obstacles where they need to rely on their intelligence. This technique is often used at the beginning of a story to show your character’s gifts and personality.

On the other hand, you might want to select specific obstacles that demonstrate an absence of a specific skill. For example, consider a male character who gets nervous around women. You can demonstrate his problem early in the story by putting him in situations where he’s forced to interact with women. Furthermore, you might consider giving the character a growth arc, where he learns to overcome this difficulty, so that by the end of the story, when in a similar situation, he’s able to cope with it in a more positive way.

Readers empathize with our characters’ struggles

The characters in your stories might battle zombies, slay dragons, or fight crime. And while your readers (probably) have never encountered the same obstacles as them, they can still empathize with your characters.

Your characters want something badly and they encounter difficulties along the way. Yet they persevere, they push through the hardship and do their best to overcome them. That’s something every one of your readers has done. They can relate to your characters’ feelings of hope and fear and they can feel the same victory (or failure) your characters do.

Pro Tip: If you’ve got writer’s block, look for more conflict and torture your characters some more.

After enduring all that conflict, we need to describe the outcome of their struggle.

Icons made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com